Deliberately going Agile

Ten years ago we all hoped for Agile to get a big breakthrough to make our software, our products, our work-life, so much better. Well Agile took off, eventually, but too often just to get the Agile Checkmark™ and then go about the business as usual. Regardless of agile methodology, we have all seen random acts of agile. We need better ways to design for large scale agile transitions than putting “Agile” on business scorecards that propagate down in organizations without proper rationale. Cargo Cult Agile is no laughing matter. We need to do much better! It is not enough to claim that everyone has misinterpreted my favorite agile method but if you hire me, all the good things will come to you. We need to understand human nature especially in crowds in order to Go Agile by Design

Agile & Design – A Personal Story

Many people perceive design phases as overhead, a reaction against waterfall approaches where people without any experience of classical design work where supposed to “design” requirements and technical blueprints.

My own early experiences with design and agility were quite different. At the age of 17 I got some minor recognition as a hobbyist inventor. It was enough to land me an apprenticeship with a small innovation bureau in 1981. Three people in the core team: An industrial designer/art director, an electronics engineer/sales guy, and a programmer/digital hardware designer.

It was a profound and life-shaping experience:

- Meeting with a customer on a Wednesday or Thursday. The industrial designer sketched continuously, much like I later learned that legendary IDEO™ does. It usually took just one meeting to get very far on a collaborative design with the customer. The flexibility of pen and paper is still hard to beat with design software when the hand that holds the pen is skilled,

- If the design felt evolved enough to both designer and customer, the core team had a brain storming on how to make a working prototype in a week. Sometimes it was just a 3D model cut out of cardboard, but often an embedded product that started out with a high-finish 3D-model but in this stage dependent on some umbilical to drive the electronics from a desktop computer.

- The designer took off to a prototype shop 2 hours’ drive up north over the weekend and built a 3D-model of whatever we designed together with the customer. Usually in wood that was painted to look like other materials. Remember there was no 3D printers generally available a back in 1981.

- I the meantime, while the designer was busy with the 3D prototype, the electronics and the software guys started to build software and interfaces that would give the product life in just a few days.

- The customer came back the next Tuesday and saw a live prototype where working software often was key, although often driven by some umbilical to a desktop microcomputer since off-the-shelf Arduinos was not available 30 years ago.

I was grateful just to hang around these guys, but I sometimes also got to do some small contributions. This also set me a standard that made it hard to take a most methodology “design phases” seriously.

We have yet to see a CAD- system that beat a skilled hand with pen and paper. You claim otherwise? Sure, most people think that something form Autocad or maybe the design tools from Adobe can berat pen and paper, hands down. Right and Wrong, actually. Once you have a something like a base design a graphics profile or similar design baseline, tools like CAD programs or vector graphics can save time as long as you are producing VARIANTS of one baseline. But if you want to quickly cover a large solution space brain-storming style, nothing beats a skilled designer quickly churning out vastly different visualization of diverse ideas with pen and paper. The cost of building a 2D or 3D representation, a model in most graphical programs is far slower each time. The difference in commitment to a particular solution between a few quick strokes with a pen and setting up some hi-fi design preview is HUGE.

Another thing I learned from these early days is that a industrial designer needs to be interested in how stuffs are made. An industrial designer needs to be curious of how many different things are put together and what makes them work. In the field of software we have seen inroads from industrial design into usability and from house architecture we got design patters. The design patters movement actually was an incubator for the agile movement.

Actually, most people have never experienced how real designers work and thus, another case of Cargo Cult. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cargo_cult.

(Don’t miss the excellent video on Cargo Cult at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qmlYe2KS0-Y )

The following almost 20 years, I suffered through cargo-cult “design activities” and a lot of other, to me, counter-intuitive practices and processes that made software painful and slow to develop.

But XP and Agile felt like getting back home to that core team in that small innovation bureau.

The best Agile teams, to me, act like a skilled industrial designer with pen and paper. They can quickly explore a large solution space to find the best solution without spending too much upfront effort. Between the team members, they know about a plethora of solutions to throw at a wide variety of problems. We go deeper into the topic of having solutions in store in another artice on Makers, Tinkering, et al at XP2012.

For now: Lets go Agile – by Design!

Erik Lundh

General Chair

XP2012 -Agile by Design

The original Agile/Lean conference since 2000.

May 21-25, 2012 in Malmö Sweden

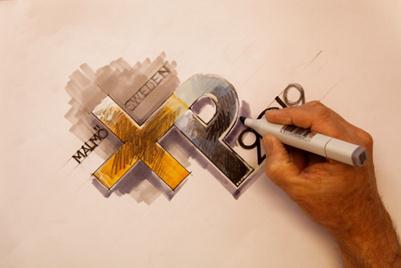

The XP2012 logo is designed by Åke Karlsson, the very same industrial designer that gave me my first shot at professional product development 30 years ago. You can watch the stop motion of how Åke works that we shot in April 2011 to illustrate my announcement of xp2012 in Madrid at xp2011: http://xp2012.org/video .

The rig was designed and built by Erik with inexpensive material that was repurposed. The Canon EOS50D DSLR was operated by Åke himself at his own leisure. Erik built a foot-operated focus and trigger remote for the camera with electrical piano pedals from Yamaha. The piano pedals were NC when the camera needed NO, but I did not need anything more sophisticated than a few relays in a box to solve that. Åke could check that his work was in camera by looking to his right on a big flat-screen panel that was connected to the cameras HDMI output.